The ‘Edmund Fitzgerald’ and its Legacy of Shipping Safety

At memorial services and other events around the Great Lakes region in recent days, bells tolled in remembrance of those who perished in one of the most famous — and definitely consequential — supply chain tragedies in history.

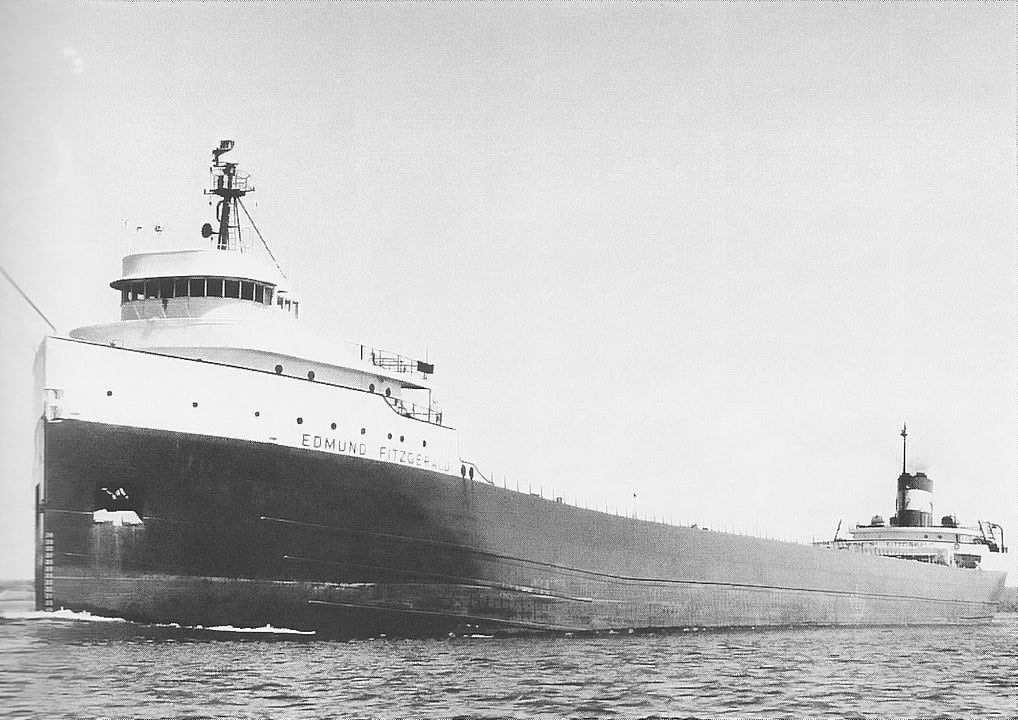

Fifty years ago Monday, the Edmund Fitzgerald sank in hurricane-force winds on Lake Superior, and all 29 men on board were lost. The Detroit-bound vessel, carrying 26,116 tons of taconite pellets for iron ore production, was on her last scheduled run of the shipping season; it also was the final voyage for captain Ernest McSorley and many of his senior officers and crew who had planned to retire.

For decades after its 1958 launch, the 729-foot-long freighter had set numerous cargo records as the largest and most magnificent on the Great Lakes. Its captain’s quarters, food service and rooms for VIP passengers were said to rival first-class accommodations on ocean liners.

After it sunk, it was found in two pieces on the Superior’s sediment days later. That it split in two is one of the few details from the sinking that have been confirmed.

The many unknown circumstances are the focal point of the ship’s legend, immortalized most notably in “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” the 1976 hit song by Gordon Lightfoot, and most recently in The Gales of November: The Untold Story of the Edmund Fitzgerald, John U. Bacon’s book that is currently climbing bestseller lists.

“There are three or four theories on why the Fitzgerald sank, and they’re all plausible theories,” Matthew Collette, professor of naval architecture and marine engineering at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan, said in a press release. “It’s really hard now, 50 years after the fact, to disentangle what really happened. That’s the reason people love the Fitzgerald — it’s a mystery.”

The memory of the Edmund Fitzgerald’s crew is sustained by the tight-knit community of maritime shipping crew members and their families and friends. Remembrance services feature a bell tolling 29 times in their memory, which has been honored by the sweeping reforms that have transformed shipping safety and supply chain operations across the region.

Those improvements have been so effective that the Edmund Fitzgerald is not only the most famous commercial vessel to sink in the Great Lakes, but half a century later, it’s also the last.

The Unforgiving Great Lakes

One of America’s greatest economic engines of the 20th century, Great Lakes shipping formed the backbone of the nation’s industrial supply chain by linking the Midwest’s raw materials — including Minnesota iron ore, Pennsylvania coal and Midwest grain — with manufacturing and export hubs. The more than 6,000 ships that have sunk on lakes Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie and Ontario are a testament to the risks.

Despite being inland and smaller in size than oceans, the Great Lakes are considered more treacherous, with waves steeper and coming from multiple directions due to the closer shorelines. Rapidly changing weather exacerbates such dynamics and intensifies “the gales of November,” the Lightfoot lyric that inspired the title of Bacon’s book.

“The ocean sailors just laughed at us. But not for long,” John Hayes, a veteran engineer on the Atlantic Ocean and Great Lakes, told Bacon. “Once they saw the Great Lakes for themselves, they shut up pretty fast — and then they started looking for safe harbor. I’m telling you, it’s not even close — and anyone who’s sailed on both would tell you the same.”

That was the backdrop as the Fitzgerald departed Superior, Wisconsin on November 9, 1975, amid a storm moving down from Canada, typical for that time of year. However, a low-pressure system approaching the Great Lakes from the southwest became increasingly problematic, and the National Weather Service issued gale warnings fueled by winds forecast for up to 60 miles per hour.

McSorley and his captain counterpart on the nearby Arthur M. Anderson prudently opted for a longer, more Northern route to use the Canadian shoreline for protection. But that gave the merging storms more time to brew, and when the vessels turned south on November 10 to approach Whitefish Bay and the Soo Locks, their broadsides were exposed to waves that were gaining strength.

Shortly after 5:30 p.m., McSorley reported to the Avafors, a Swedish ship, “I have a bad list, lost both radars. And am taking heavy seas over the deck. One of the worst seas I’ve ever been in.” At 7:10, the captain radioed the Arthur M. Anderson, “We are holding our own.” Five minutes later, the Edmund Fitzgerald disappeared from radar.

Technology and Regulatory Improvements

Evolving technologies have made maritime shipping safer, but the Edmund Fitzgerald provided regulatory pushes. Investigations and reports by the U.S. Coast Guard’s Marine Board of Inquiry in 1977 and the National Transportation Safety Board the following year set many of the changes in motion.

In the 1970s, freighters relied on sparse radio weather reports and paper charts. The Fitzgerald sailed without accurate forecasts, modern radar or distress beacons. Its loss led to a major modernization push: Weather data buoys were deployed across the Great Lakes beginning in 1979, and by 2019, nearly 60 provided real-time wind, wave and temperature data.

Satellite tracking, automatic identification systems and emergency position-indicating radio beacons now ensure vessels’ locations and distress signals are immediately known. Updated electronic mapping, stricter load limits, better inspections and expanded Coast Guard response units have greatly improved safety.

Vessels have traditionally been built longer to hold more cargo between the bow and stern. As a result, Bacon notes in his book, crew members noticed that the Fitzgerald became pliable, sometimes frighteningly so, in rougher seas.

Over the years, the ships’ construction and steel quality haven’t changed much, but load (or Plimsoll) line regulations were re-examined to ensure more distance from the waterline to the main deck, making vessels less vulnerable to taking on water. Many ships, including the Fitzgerald, were known for regularly cheating Plimsoll lines, enabling them to carry hundreds of tons more cargo over the course of a shipping season.

Travis Martin, president of Bay Engineering, Inc., a Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin-based naval architecture and marine engineering firm, told Traverse City, Michigan TV station WPBN that he believes modern ships would have withstood the conditions that periled the Fitzgerald.

“(A vessel is) going to be loaded more conservatively,” he said. “It’s going to be built more survivable. … (S)afety is built in. There hasn’t been a sinking in over 50 years, and there’s a reason for that, I think, due to some of the improvements in design standards and operational standards that were implemented at that time.”

Lightfoot’s song states, “Superior, they said, never gives up her dead.” But the 29 men aboard the Fitzgerald didn’t perish in vain — the safety regulations written in their blood, as well as the integrated forecasting, navigation and communication systems have made Great Lakes shipping far more efficient, resilient and especially safe.

And that is the Edmund Fitzgerald’s greatest legacy.