Inside Supply Management Magazine

ROB Roundup: April PMI®

As this space has mentioned previously, Institute for Supply Management® typically shies from making proclamations or projections on what the ISM® Report On Business® data means for the overall economy, preferring to let the numbers speak for themselves. On Friday, a grand pronouncement was unavoidable, because the April PMI® numbers spoke so forcefully.

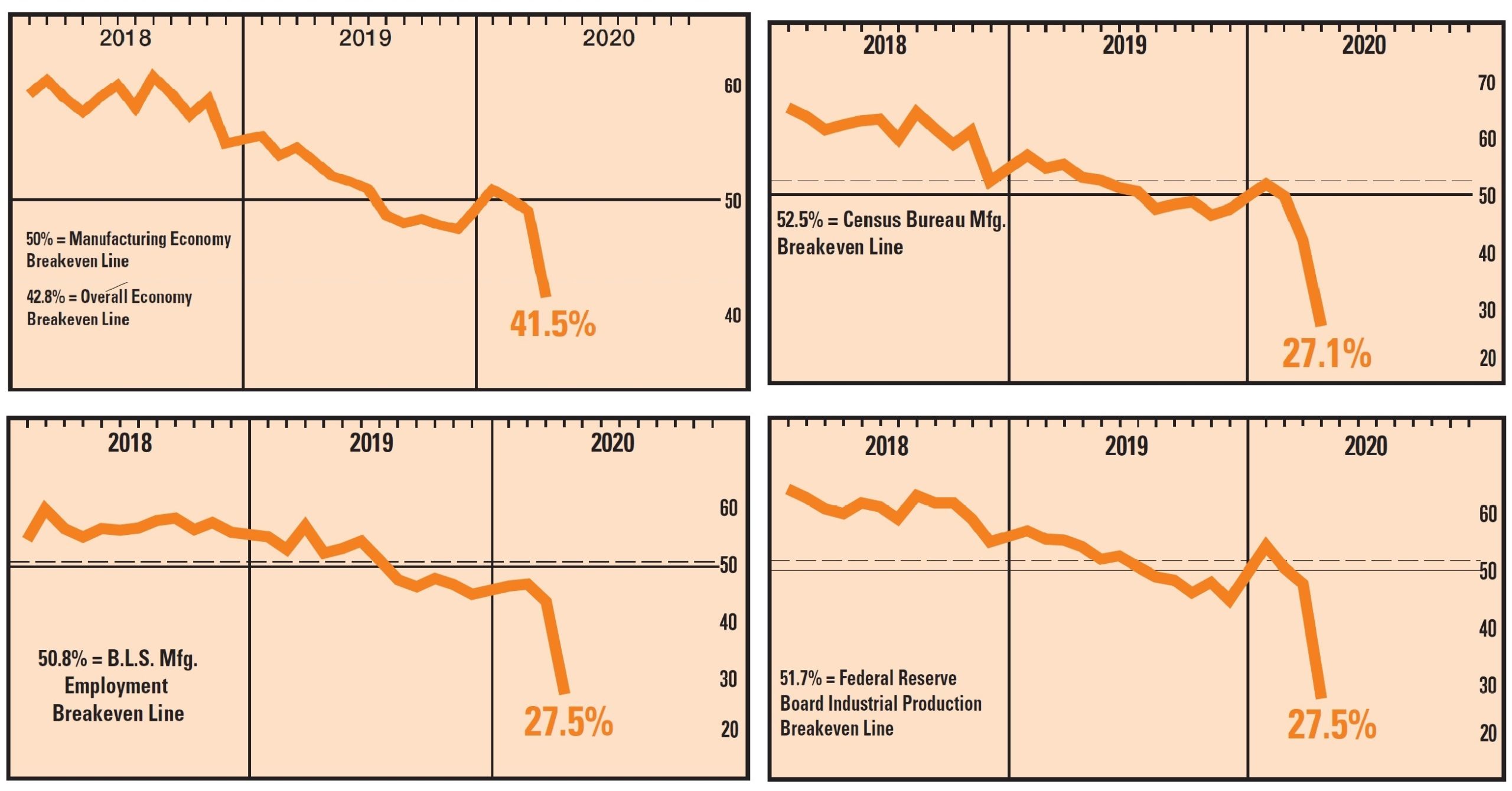

Clockwise, from top left: The April PMI®, New Orders Index, Production Index and Employment Index in monthly chart form

Clockwise, from top left: The April PMI®, New Orders Index, Production Index and Employment Index in monthly chart form

The composite index reading of 41.5 percent indicated that the coronavirus (COVID-19)-ravaged U.S. economy fell into contraction after 131 consecutive months of growth, and some elements of the manufacturing sector have hit historic lows. On a conference call with reporters, Timothy R. Fiore, CPSM, C.P.M., Chair of the Institute for Supply Management® Manufacturing Business Survey Committee, offered a dramatic but distinct summation: “The data supports the fact this is the fastest rate of change in economic activity in modern times.”

May is gonna be all about discovering how bad April was. ISM Manufacturing Index headline lowest since 2009; production lowest ever; employment lowest since 1949.

— Michael McKee (@mckonomy) May 1, 2020

Yeah, April was bad.

The subindexes and Business Survey Committee members’ comments were even more sobering. Harry S. Truman was president the last time the Employment Index (27.5 percent) was this low. The Production Index hit its all-time floor, the lowest (27.5 percent) reading since numeric Report On Business® index figures were first kept in January 1948. Additional context was provided by the degrees of fluctuation, as exemplified in the above charts. The New Orders, Production, Employment and Supplier Deliveries indexes had their biggest one-month percentage-point changes in generations.

Business Survey Committee respondents described how the pandemic has impacted their companies’ production (a chemicals business is now making only hand sanitizer), processes and profits. Wrote a respondent in nonmetallic mineral products: “COVID-19 has destroyed our market and our company. Without a full recovery very soon, as well as some assistance, I fear for our ability to continue operations.”

"The 15.1-percentage point decrease in the New Orders Index between March and April is the largest one-month decline since April 1951." - @ism

— Caroline Baum (@cabaum1) May 1, 2020

However, Fiore said, unlike March, the April PMI® data is tangible enough for executives and supply managers to formulate mitigation plans and recovery strategies. “We couldn’t see the cliff in March,” Fiore said. “I don’t think we’re at the bottom of the hill, but the difference now is that we can see it.” He said that means at least six weeks of contraction conditions before the start of a slow rebuild — especially for factories that must implement social distancing and other protections for workers. In workplaces with high rates of infection like meat- and poultry-processing plants, that timetable is even longer.

“As we enter May, this is a true indication of what is happening in the manufacturing economy,” Fiore said. “We can now understand the trajectory, the degree of change, how it’s affecting market sectors and how long extreme measures will persist. March’s rate of change was too rapid for a monthly survey to capture the full impact, but I believe April has brought a level of stability that make monthly information much more valuable — invaluable, in fact.”

"The details are significantly worse than the headline." @IanShepherdson on U.S. ISM Manufacturing Survey, April #PantheonMacro

— Pantheon Macro (@PantheonMacro) May 1, 2020

The Supplier Deliveries Index hit 76 percent, its highest level since April 1974 (82.1 percent), when headlines were dominated by Watergate and shortages of commodities like steel, textiles and vinyl. Since February, ISM has diligently explained and reminded that Supplier Deliveries is the only Report On Business® index that is inversed, as a reading above 50 percent indicates slower deliveries, which typically signals high demand and healthy consumer spending.

However, the recent elevated Supplier Deliveries numbers — which have limited the PMI®’s decrease — are the result of coronavirus-related supply problems. That dynamic was illustrated in a part of the Manufacturing ISM® Report On Business® that is often overlooked: the Buying Policy section that documents lead times. The ISM® Glossary of Key Supply Management Terms defines lead time as “the time that elapses from placement or an order until receipt of an order, including time for order transmittal, processing, preparation and shipping.” In April, lead times for capital expenditures and production materials decreased.

The ISM manufacturing index fell less than expected in April, to 41.5 vs expected of 36. But don’t be fooled, a slowdown in “supplier deliveries” held the index up. In normal times this would indicate overwhelming demand. Now, it signals disruptions in the supply chain.

— Brian Wesbury (@wesbury) May 1, 2020

“From a pure demand and material-conversion standpoint, discounting the oversized influence in the ability to obtain supply, the economic contraction in April was likely sharper than the traditional PMI® calculation indicates,” Fiore said.

The Report On Business® roundup:

Associated Press: U.S. Manufacturing Falls in April as Virus Ravages Economy. “The news was bad across the board: Production, new orders, hiring and export orders all fell faster in April than they did in March. ‘The underlying details indicate a severe downshift in activity as production and employment contracted at a record pace,’ economists Oren Klachkin and Gregory Daco of Oxford Economics wrote in a research report. ‘New orders signal that activity is unlikely to improve in the near term.’ Economists had expected an even bigger drop.”

With Americans staying closer to home, there were two sectors that were bright spots in April, with increased production—food, beverage and tobacco products and paper products. That should be a surprise to no one.

— Chad Moutray (@chadmoutray) May 1, 2020

Bloomberg: U.S. Factory Output Shrinks at Record Pace, ISM Gauge Shows. “(T)he latest figures indicate an economy that’s rapidly deteriorated into a recession. ISM’s headline manufacturing measure fell less than forecast — a more-moderate 7.6-point decline to an 11-year low of 41.5 — supported by a further increase in delivery times. While longer lead times can often indicate elevated demand, the highest supplier deliveries index since 1974 reflects virus-related disruptions in supply lines and business closures.”

CNBC: ISM Manufacturing Index Beats Expectations in April at 41.5. “I’m actually pretty stunned by this,” analyst Rick Santelli said. “I was preparing for something much smaller. It’s the weakest level nonetheless since 2009, but many thought it would be in the 30s. Even though it wasn’t a terrific number, it's better than expected. Let’s go through some of the internals: (The New Orders Index) really is about what we expected, 27.1. ... You would expect that would not be surging, you would think manufacturing would far better than services (because) we’ve shut everything down.”

MarketWatch: New Orders Reading in Key ISM Factory Index Is at Its Worst Since the 1950s. “The details of the report were grim. The index for new orders dropped 15.1 points to 27.1 percent, the biggest monthly drop since 1951. … Only a rise in supply deliveries index kept the index from falling even deeper, economists said. What’s more, 16 of the 18 industries tracked by ISM reported declines. That’s another bad sign. Only paper products and foods products rose in April.”

Here's the spread between new orders and inventories in the US manufacturing PMI data. By far the lowest new orders compared to inventories since the war. This is, indeed, an extreme event. pic.twitter.com/bWFrV0FskS

— John Authers (@johnauthers) May 1, 2020

Reuters: U.S. Manufacturing Activity Plunges to 11-Year Low as Orders Sink. “(The PMI) added to a raft of grim data this week, including a collapse in consumer spending in March and a surge to 30.3 million in the number of Americans who have filed claims for unemployment benefits in the last six weeks. Strict measures to slow the spread of COVID-19, the respiratory illness caused by the coronavirus, have almost paralyzed the country, leading to the deepest economic contraction since the Great Recession in the first quarter.”

The Wall Street Journal: Coronavirus Prompts Biggest U.S. Manufacturing Pullback Since Last Recession. “Fiore said he saw signs that the decline in factory activity was starting to bottom out. But the road back is going to be long and slow, he said. … Fiore said he expected the economy to start reopening in May and June. But it will take a long time for consumers to feel comfortable going out again, he said, which means it will take a long time for demand for factory goods to pick up.”

The US ISM manufacturing index fell to 41.5 in April, which was far better than the 36.9 consensus estimate. However, the bigger focus will be on the non-manufacturing ISM released next week pic.twitter.com/KuMgvAUoys

— MacroMarketsDaily (@macro_daily) May 1, 2020

The Non-Manufacturing ISM® Report On Business® will be released on Tuesday. Also, ISM’s Spring 2020 Semiannual Economic Forecast for the manufacturing and non-manufacturing sectors will be released on May 15. For the most up-to-date content on the PMI® and NMI® reports, use #ISMROB on Twitter.